In this op-ed for commonspace.eu, Vasif Huseynov says Armenia has no right to occupy the moral high ground on humanitarian issues in the South Caucasus. If really interested in peace and reconciliation, both sides should condemn crimes against humanity including war crimes and hold the perpetrators accountable instead of denying the facts, he says. “The establishment of a mutually agreed mechanism to investigate war crimes and address the concerns of the people directly affected by them could be an important element that can be included in a peace treaty”, he argues.

“I am certain that the Armenian forces have never committed such war crimes”, tweeted Edmon Marukyan, Ambassador-at-Large at Armenia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and leader of Bright Armenia political party, in reference to a video which allegedly shows Azerbaijani soldiers executing Armenian prisoners of war. Considering the 30 years of history of the conflict, the massacre of hundreds of innocent Azerbaijanis in Khojaly (1992), the ethnic cleansing of more than 700 thousand Azerbaijanis from the formerly occupied territories, the remaining unclarity about the fate of around 4000 Azerbaijanis who went missing or taken hostage, Azerbaijan’s unearthing of increasingly more areas in liberated Karabakh territories where Azerbaijani soldiers and civilians have been buried summarily, it is shocking to hear such statements of Armenian officials who deny all this history and claim to righteousness and the moral high ground. It is particularly disturbing for Azerbaijanis like me who were subject to such atrocities and forced displacement three decades ago in the course of the First Karabakh War and afterwards.

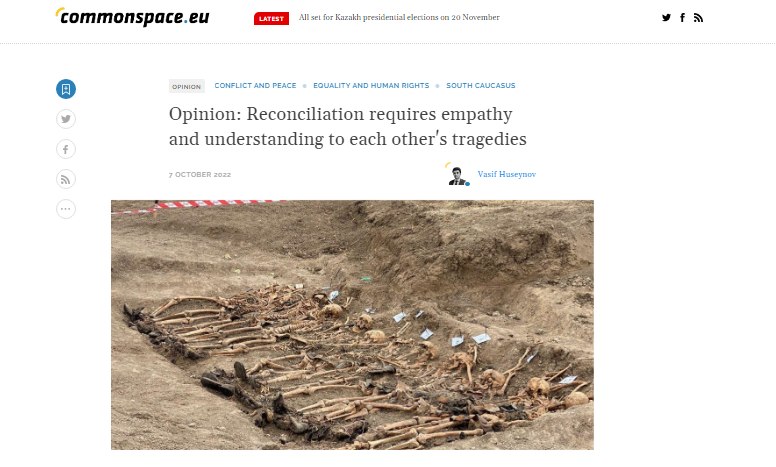

A few days after the emergence of the above-mentioned video, another mass grave belonging to the First Karabakh War was discovered by Azerbaijanis in Edilli village of Khojavand. The skeletons were identified to be servicemen from their clothing with their hands and feet being tied with wire and rope. Similar mass graves have been found in many other parts of the Karabakh region including in Bashlibel village of Kalbajar where civilians, who couldn’t leave their homes “in time” before Armenian troops stormed into the village, were shot down en masse.

If really interested in peace and reconciliation, both sides should condemn such crimes against humanity including war crimes and hold the perpetrators accountable instead of denying these facts. The approach held by Armenian leaders like Edmon Marukyan is therefore unacceptable and extremely detrimental to peace and security between the two countries. Unfortunately, such reaction was noticed in the reaction of other Armenian observers but more surprisingly also in that of Western politicians and institutions.

For example, a recent session at the European Parliament with High Representative Joseph Borrell on October 4 about the policies of the European Union (EU) towards the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process was distressingly one-sided to the extent that it sounded as if one listens to the Armenian parliament rather than to the Parliament of 27 European nations. Not a single member of the parliament voiced the concerns of the Azerbaijani side. Nor did Mr. Borrell who called territories occupied by Armenia during the first Karabakh War as “disputed areas”, while calling the area of the latest hostilities unequivocally “Armenian territory” – disregarding that the territories which he calls “disputed” are internationally recognized as belonging to Azerbaijan and as such are not “disputed” under international law.

Nor did the Azerbaijanis never see European politicians wearing the signs of “Stand with Azerbaijan” while their internationally recognized territories were under illegal occupation, destroyed and looted for 30 years – quite to the opposite to the scenes now shared from some European countries where MPs or Ministers appear with the signs of “Stand with Armenia”.

Certainly, this is not a novelty. In the course of the First Karabakh War, at the insistence of France, the perpetrators of the invasion of the Azerbaijani territories were mentioned as “local Armenian forces” (i.e., not Armenia as a State) in the resolutions of the UN Security Council and the conflict was treated not under the Chapter VII of the UN Charter as an “act of aggression,” but under the weaker Chapter VI as a dispute that should be settled peacefully. Persisting this anti-Azerbaijani bias, both chambers of the French Parliament recognized so-called “Nagorno-Karabakh Republic” in late 2020 although this entity was never recognized by Armenia itself.

This disregard by Armenian politicians to the tragedies of the Azerbaijani side and the partisan approach of parts of the political elite in western countries has been a major obstacle to the peaceful resolution of the conflict and continues to dramatically undermine current peace efforts. Indeed, the recent escalation between the two South Caucasian countries and the subsequent developments once again demonstrated how difficult the peace process is, and alarmingly reminded that peace cannot be achieved immediately, even if the sides agree on the text of a peace treaty. Although a political agreement is necessary to build peace between the two peoples, but more general reconciliation necessitates empathy and understanding to the tragedies each side was subject to due to this conflict. For this purpose, the establishment of a mutually agreed mechanism to investigate war crimes and address the concerns of the people directly affected by them could be an important element that can be included in a peace treaty.