The protection of minority rights is one of the best-explored cross-disciplinary issues in the social sciences and humanities. A vast literature exists that deals with this subject from different angles, including those of international law, sociology, history, cultural anthropology, political science, and so on. According to Francesco Capotorti, Special Rapporteur of the United Nations Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, a minority is “A group numerically inferior to the rest of the population of a State, in a non-dominant position, whose members— being nationals of the State-possess ethnic, religious or linguistic characteristics differing from those of the rest of the population and show, if only implicitly, a sense of solidarity, directed towards preserving their culture, traditions, religion or language”1 .

History provides many examples of times when minority groups were at the epicentre of internal strife and ethnic conflicts. They are typically mobilized by various irredentist or separatist movements. Sometimes, kin-states also assist them in their struggles. Basques and Catalans in Spain, Scots and Catholics of Northern Ireland in Great Britain, Abkhazs and South Ossetians in Georgia, and ethnic Armenians of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) in Azerbaijan are well-known examples of such minority groups. In fact, it was the irredentist Karabakh movement, which, in 1988 in Armenia and the NKAO, started advocating for the unification of the NKAO with Soviet Armenia, that was behind the mobilization of Nagorno-Karabakh ethno-nationalists who demanded the transfer of this mainly Armenian-dominated region from the jurisdiction of Soviet Azerbaijan to Soviet Armenia.

Despite the rejection of the NKAO’s appeal by Soviet Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh ethno-nationalists did not relinquish their claims and eventually became locked in a tense stand-off with Azerbaijan. Nor did neighbouring Soviet Armenia’s stance help. In fact, when the Soviet leadership attempted in vain to deal with this conflict, Soviet Armenia’s continuous support of the Nagorno-Karabakh ethno-nationalists made its resolution impossible.

After Azerbaijan and Armenia regained their independence in 1991 following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Republic of Armenia continued its meddling in the internal affairs of Azerbaijan. In order to avoid accusations of irredentist claims, this kin-state, together with its kindred in Nagorno-Karabakh, started to demand the right of people of Nagorno-Karabakh to self-determination and separation from Azerbaijan. United around the Karabakh issue, representatives of the Armenian Diaspora in the U.S.A., France, and other states also played an instrumental role in providing the necessary political, economic, financial, and information support for the Republic of Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh ethno-nationalists.

The Armenian Diaspora has, over the years, also worked very hard to misrepresent the nature of the Armenian–Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. One of the successes of this policy was the adoption by the U.S. Congress in October 1992 of the notorious Section 9072 of the Freedom Support Act (FSA), initiated by the Armenian-American lobby in retaliation to Azerbaijan cutting off the rail route that carried supplies and fuel to Armenia in 1992. As a result of this amendment, Azerbaijan became the only post-Soviet state not to receive direct aid from the United States government to facilitate economic and political stability. However, perhaps nobody in the U.S. Congress knew, when they adopted section 907 of FSA, that by that time Armenian armed forces had already committed the Khojaly massacre on the night of February 25–26, 1992; 3 captured Shusha, a main city of the Azerbaijani-populated administrative district within the former NKAO, on May 8, 1992; and seized Lachin, the first adjacent Azerbaijani district located between Armenia and the former NKAO, on May 18, 1992. Therefore, “Armenians were aggressively at war with Azerbaijanis who considered it national suicide to provide supplies to neighbours that were carrying out military action against them”4.

There is also independent opinion that “the US argument is invalid, based upon a misconstruction of the conflict, because “as a matter of fact, Azerbaijan has the right to protect itself against a country with which it considers itself at war. Whether Armenia accepts this claim is irrelevant”5.

Thus, it is crystal clear that, owing to the greater Armenian institutional presence in Washington, D.C., and a lack of serious opposition from the Azerbaijani side, along with the fact that American national interests were not perceived as being at stake at that moment, the Armenian-American lobby was able to successfully frame the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in line with their homeland’s interest and transform Azerbaijan’s attempts to reassert control over its territory into an act of ‘aggression’ by Azerbaijanis and combine it with the threat of a ‘second genocide’ against the Armenians. 6

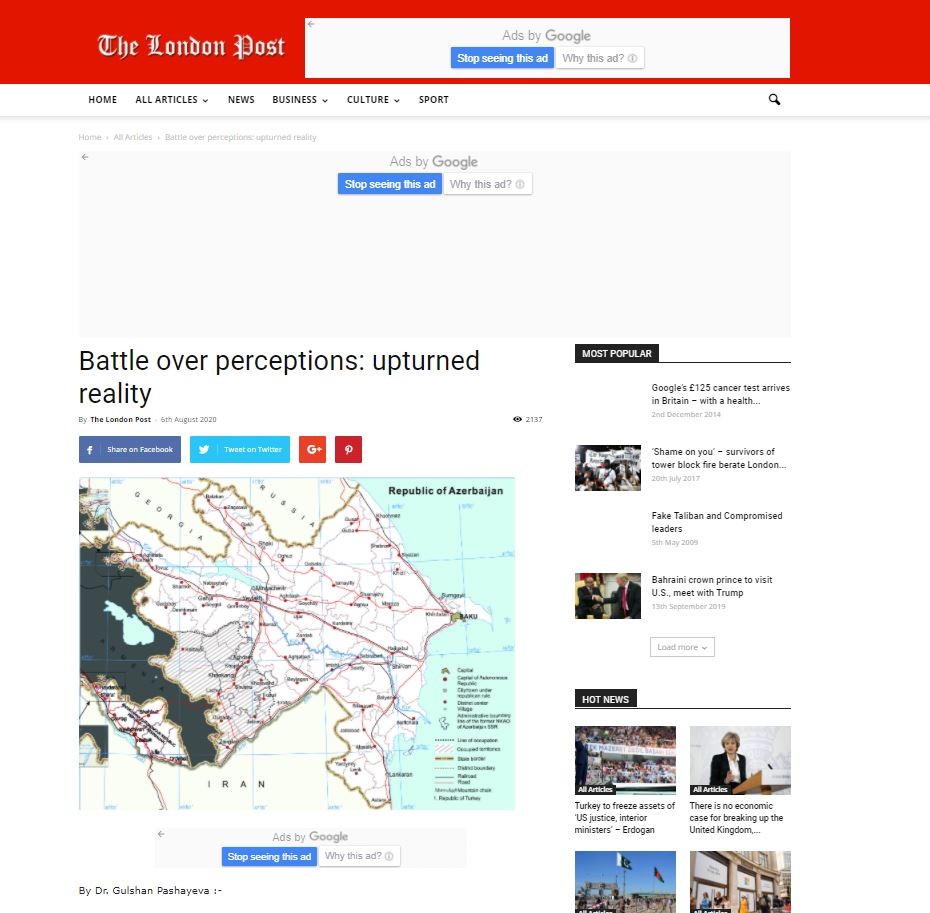

When a ceasefire agreement was signed in May 1994, the facts on the ground were quite the opposite. In fact, aggression by Armenians was committed against Azerbaijanis. Not only was close to one-fifth of the internationally recognized territory of Azerbaijan, consisting of nearly all the territory of the former NKAO and additional seven adjacent Azerbaijani administrative districts (Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Fizuly, Jabrail, Kubatly, and Zangilan) that had never been populated by Armenians occupied, but also the entire Azerbaijani population of these territories was ethnically cleansed by the Armenian armed forces. More than 20,000 Azerbaijanis were killed and around one million displaced in the course of this armed conflict’, 7.

The OSCE has been involved in the mediation efforts of Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh since March 1992. “The Minsk Group, the activities of which have become known as the Minsk Process, spearheads the OSCE’s efforts to find a peaceful solution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. It is co-chaired by France, the Russian Federation, and the United States”8.

However, throughout the years, the mediation efforts of the OSCE Minsk Group were reactive, rather than proactive. Despite the fact that co-chairs of the Minsk Group more than once declared the status quo unacceptable they have mainly focused on preventing an escalation of the conflict, rather than making a resolution happen. Therefore, it is unsurprising that in his interview on 9 July 2020, President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev while giving a broad insight into the settlement process of the Armenian-Azerbaijan conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh accused the OSCE Minsk Group for its inaction on Armenia’s illegal occupation of Azerbaijani lands. According to the President this conflict must be resolved within the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan.

“The establishment of a second Armenian state on Azerbaijani lands will never be allowed. All occupied lands must be liberated from the occupiers, and Azerbaijani citizens must return to the lands of their ancestors. This is a principled position, and the world community supports this position”9.

Indeed, the leading world and regional powers and international organizations recognize the territorial integrity and the inviolability of Azerbaijan’s borders. However, they oppose any attempts to use any sanction against Armenia, merely paying lip service to the readiness to act as guarantors of a final settlement in case Armenia and Azerbaijan find mutually acceptable compromises on their own. In fact, owing to the lack of political will of the international community, the four legally binding UN Security Council resolutions (specifically, 822, 853, 874 and 884) adopted in 1993 demanding full and unconditional withdrawal of the Armenian armed forces from the occupied territories of Azerbaijan have not yet been implemented by Armenia. Thus, only ethnic Armenians live in the decimated Azerbaijani towns and villages of the former NKAO and the above-mentioned seven districts at present.

At the same time, the separatist regime created in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan, which has not been recognized by any other state, including its kin-state Armenia, has been working very hard, together with Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora, toward the illegal resettlement of thousands of Armenians in the occupied Azerbaijani territories as well as the implementation of illegal activities and infrastructure projects there. They have also been pursuing a policy of distorting the origin and the use of Azerbaijani monuments in the occupied territories. In fact, deliberate destruction and pillage of the cultural heritage as well as religious and historical monuments is a part of their battle over perception.

“Almost all once Azerbaijani-populated towns, villages, and even streets, have been renamed after the occupation, and Armenianized, in a vicious attempt to erase any traces of Azerbaijanis’ age old presence in Karabakh” 10.

Thus, this ugly reality, which emerged as a result of the use of military force and the expulsion of Azerbaijani inhabitants in violation of many principles of public international law, as well as international humanitarian law, is a vivid manifestation of the irresponsible demand of Nagorno Karabakh ethno-nationalists for self-determination (in fact, for secession). What nobody takes into consideration is that the implementation of their so-called right to self-determination led to the abuse of the rights of the around 700,000 Azerbaijani IDPs, – former inhabitants of the former NKAO and seven adjacent Azerbaijani districts. In fact, these people forcibly expelled from their places of origin are the Azerbaijanis of historic Karabakh region’ 11.

Geographically, this region can be divided into mountainous Karabakh, which consists of the highlands of the Karabakh Range of the Lesser Caucasus, and lowland Karabakh, located between the rivers Kura and Araks. Unlike Armenians, Azerbaijanis have never historically differentiated between the lowland and mountainous parts of the historic Karabakh region, but have perceived it “as a single geographical, economic and cultural space, where they have always been politically and demographically dominant”. Moreover, many Azerbaijanis considered the creation in 1923 of the NKAO within ‘artificial’ (i.e. previously non-existent) borders an attempt to secure “an Armenian majority region within Azerbaijan as part of the Soviet/Russian policy of divide and rule” 12.

According to the last USSR census of 1989, the population of NKAO residing in the mountainous part of the historic Karabakh region consisted of 189,100 people, of whom 145,500 were Armenians (76.9 percent), 40,688 Azerbaijanis (21.5 percent), and 2,912 Russians and other nationalities (1.6 percent).13

Azerbaijani inhabitants were a minority within NKAO; however, the population of the other mountainous and lowland parts of the Karabakh region was predominantly Azerbaijani before this armed conflict. Today, the entire historic Karabakh region, which includes the territory of the former NKAO and seven adjacent districts, is under occupation by Armenian military forces. The most vulnerable and affected by this conflict Azerbaijani inhabitants of these territories are the direct victims of the Armenian aggression. Their voices, it seems, have not been heard very often over the years. Their views and aspirations, as well as their human stories, have not been illuminated in the glossy magazines or famous international television channels. Seemingly, they have not been in the limelight of the international media. The fundamental rights of these innocent civilians, forcibly expelled from their homeland, have been violated for almost three decades. Azerbaijanis from Karabakh “have not been able to exercise their basic human rights and return to their homes. Instead, internally displaced, they are scattered across Azerbaijan, hoping for peace and coexistence with their Armenian neighbours as they had before” 14.

However, the recent outbreak of violence that happened in the Tovuz region of Azerbaijan along the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan on 12-14 July 2020 proves once more the dangerous destructive potential of this unresolved conflict. According to Hikmat Hajiev, head of the foreign affairs department of Azerbaijan’s presidential administration by committing this border provocation Armenia tried to derail the negotiation process by all means, evade responsibility for the occupation of Azerbaijani territories – Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent regions and create a new source of tension and conflict in the state border between Armenia and Azerbaijan and involve the political-military organization of which it is a member, into this conflict’, 15.

Needless to say, that Armenia is the only state in South Caucasus that is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Russia-led military bloc and in fact, after the fighting broke out, Armenian officials appealed to the CSTO to get involved’, 16.

However, despite the fact that CSTO announced that it would convene an extraordinary session on July 13, this meeting was cancelled later on. One might assume from this logic that there is again an attempt to mislead the international community and misrepresent the truth.

Therefore, as a very first step, an international reaction is urgently needed to put an end to Armenia’s “syndrome of impunity.” First of all, consolidated actions should be agreed upon to eliminate the consequences of the Armenian occupation of close to one-fifth of the internationally recognized territory of Azerbaijan and clear-cut arrangements should be made to ensure a safe and dignified return of the expelled Azerbaijanis of the historic Karabakh region to their places of origin. Next, the solution to this conflict undoubtedly lies in coexistence and cooperation, both between Armenia and Azerbaijan and between the Karabakh Armenians and the Karabakh Azerbaijanis. The international community should help in this context and promote civil initiatives involving direct contacts not only between Armenian and Azerbaijani representatives, but also between Karabakh Armenians and Karabakh Azerbaijanis’, 17.

Finally, an equal and just approach should be demonstrated by the international community to all the inhabitants of the historic Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, irrespective of their ethnic origins. Thus, the final status of this region, to be defined within the internationally recognized borders of Azerbaijan, as well as security measures equally acceptable to both Armenian and Azerbaijani inhabitants of the historic Karabakh region, should be carefully elaborated within a comprehensive solution to this conflict.

https://www.academia.edu/43801483/Battle_over_perceptions_upturned_reality

References:

1 Francesco Capotorti. Study on the Rights of Persons belonging to Ethnic, Religious, and Linguistic Minorities. United Nations, New York, 1979, p.96, para 568 – https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/10387?ln=en

2 After Azerbaijan’s unequivocal support of the US’s Global War against Terror (GWoT) in 2002, the Bush Administration urged and eventually secured a de facto repeal of Section 907 through annual Presidential waivers ensuring Baku’s role as a key ally in the GWoT. Nevertheless, Section 907 has not been repealed completely so far due to the continuous resistance of the Armenian-American community.

3 This tragic event resulted in the death of 613 people, including 106 women, 63 children and 70 elderly people with the assistance of servicemen of Infantry Guards Regiment No. 366 of the former Soviet Union. In addition, 487 people were wounded, including 76 children; 1275 people were held hostage; and 150 people were reported missing.

4 U.S. Congress Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act. U.S. Denies Aid to Azerbaijan. In: Azerbaijan International, summer 1998 (6.2), p.28. Available at: http://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/62_folder/62_articles/62_section907.html

5 Svante E. Cornell. Undeclared war: The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict reconsidered. In: Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, vol. XX, No 4, Summer 1997, p.11. Available at: https://isdp.eu/content/uploads/images/stories/isdp-main-pdf/1997_cornell_undeclared-war.pdf

6 Thomas Ambrosio. “Congressional Perceptions of Ethnic Cleansing: Reactions to the Nagorno-Karabakh War and the Influence of Ethnic Interest Groups.” In: The Review of International Affairs, vol. 2, no. 1, autumn, 2002, pp. 24– 26.

7 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

8 Available at: OSCE Minsk Group. Available at: https://www.osce.org/mg

9 Azerbaijan President Criticizes OSCE Minsk Group Inaction On Armenia’s Illegal Activities. Caspiannews.com, July 9, 2020. Available at: https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/azerbaijan-president-criticizes-osce-minsk-groupinaction-on-armenias-illegal-activities-2020-7-7-39/

10 Nasimi Aghayev. Armenia: Cultural Genocide, Denial and Deception. Medium.com, 6 July 2020. Available at: https://medium.com/@nasimiaghayev/armenia-cultural-genocide-denial-and-deception-7a1051929ffe

11 Assessing the severity of displacement. Thematic Report. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. February 2020, p. 18. Available at: https://www.internaldisplacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/Severity%20Report%202019.pdf

12 Tabib Huseynov. A Karabakh Azeri perspective. In: Accord. Conciliation Resources, Issue 17, 2005, p.25. Available at: https://rc-services-assets.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fspublic/The_limits_of_leadership_Elites_and_societies_in_the_Nagorny_Karabakh_peace_process_Accord_Issue_1 7.pdf

13 Goskomitet SSSR po statistike. Itoqi vsesoyuznoy perepisi naseleniya 1989 qoda, Moskva, 1989

14 Aybaniz Ismayilova. Dream of Azerbaijan’s ‘bronze woman’ lives on. In: San Diego Jewish World. May 8, 2020. Available at: https://www.sdjewishworld.com/2020/05/08/dream-of-azerbaijans-bronze-woman-liveson/?fbclid=IwAR2rmIVH3VWIeQ7LjZ8SF6XUg_ttlRCUFctClIIJfSJ2Tkxt375HOYLdt8s

15 Azeri official: EU should distinguish between aggressor and subject of aggression. Euractiv.com, 15 July 2020. Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/azerbaijan/interview/azeri-official-eu-should-distinguish-betweenaggressor-and-subject-of-aggression/

16 Армения ждет реакции ОДКБ на обострение на границе с Азербайджаном. Ria.ru. 13 July 2020. Available at: https://ria.ru/20200713/1574280733.html

17 Tabib Huseynov. A Karabakh Azeri perspective. In: Accord. Conciliation Resources, Issue 17, 2005, p.27. Available at: https://rc-services-assets.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fspublic/The_limits_of_leadership_Elites_and_societies_in_the_Nagorny_Karabakh_peace_process_Accord_Issue_1 7.pdf

(Dr. Gulshan Pashayeva specializes in conflict resolution and security studies, as well as gender and language policy)